In this post I talk about my photographic art practice and how this has allowed me to produce new relationships between myself, other people and the world. I then discuss the role of visual images in artistic experimentation and how this interconnects with the use of visual imagery in pedagogical documentation or inquiry-led learning practices in early childhood education.

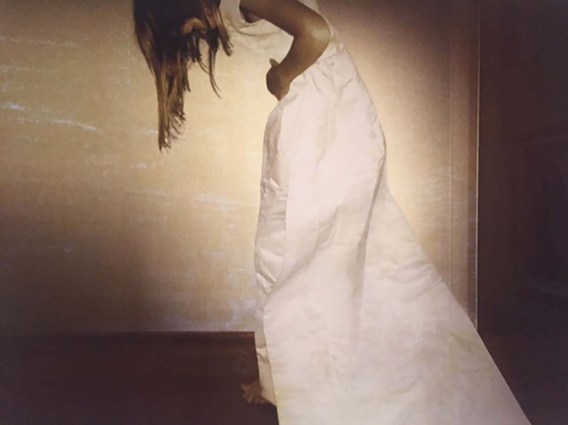

Experimention and learning through images has been a huge part of my life for as long as I can remember. Since I was first taught photography at school (thank you Georgina Campbell) I have experimented with a myriad of photographic processes including medium format cameras, scanners and digital photography. My photos have focused on the relationship between landscape and the subject matter’s psychological world. Creating and thinking through images has allowed me to experience things and learn in a way that could not be done with words. Learning new artistic skills, techniques and concepts has also been important in opening up new creative possibilities for further exploration. Over the years, this process has led to the emergence of new thought processes, feelings, understandings and artistic skills, generating new starting points for further experimentation.

I think that my love of image making and my love of children’s education stems from the same place: a relentless enthusiasm to continuously think and learn through the world in new and different ways. Art has been one of the greatest forces for producing deep thinking and feelings in my life. I would love children to have this opportunity too.

Experimentation and learning through visual imagery is also a huge part of pedagogical documentation. When I take a photo or video of a child’s research process in an art museum, I always consider the lighting, the colours, the composition and wait for just the right moment to press the shutter to try and capture a particular energy, emotion or idea. To me, documenting through visual imagery is an aesthetic process. At other times, it does feel more ethnographic or slightly more removed. Recording. Logging. Taking field notes. Archiving pictures to look back on later. I guess that both artistic experimentation and pedagogical documentation are creative and analytical processes.

I often get asked if I use my own art practice with children. I always say yes and no. The inquiry-led process that drives artistic experimentation is a non-negotiable component of any children’s activity I am a part of. At the same time, I am not interested in doing photography workshops with children. I don’t really know why.

I am not exactly sure how my photographic practice and my work with children is connected but I know that it is. I guess they are related in a way that all things that are incredibly important to an individual are connected. I recently read a quote by the artist and poet Etel Adnan that said, “… my writing and my paintings do not have a direct connection in my mind. But I am sure they influence each other in the measure that everything we do is linked to whatever we are, which includes whatever we have done or are doing.” I totally get that.

The MONA building was also designed to naturally flood as the River Derwent rises over the next 50 years. When questioned about this in a 2014 Guardian article, Walsh said:

The MONA building was also designed to naturally flood as the River Derwent rises over the next 50 years. When questioned about this in a 2014 Guardian article, Walsh said: