This is a follow up to my recent post on the role of materials in children’s learning through art. If you have not read this already, I recommend checking it out before reading on.

Here I present four different organisations – a university research centre, a design consultancy, a creative recycle centre and a children’s art studio – who are all exploring materiality in new and experimental ways. I selected these organisations as I am interested in thinking about how materials are being researched and considered in a collective way, among groups of people with diverse interests, skills and expertise.

MIT Media Lab: Mediating Matter group (USA)

I am a massive fan girl of the MIT Media Lab. For those of you who are not unfamiliar with this university research centre, it is an interdisciplinary lab ‘that encourages the unconventional mixing and matching of seemingly disparate research areas’ (MIT website, 2018). I have always seen the Media Lab as an epicentre for innovative and ground-breaking work across a myriad of disciplines such as art, technology, design and education.

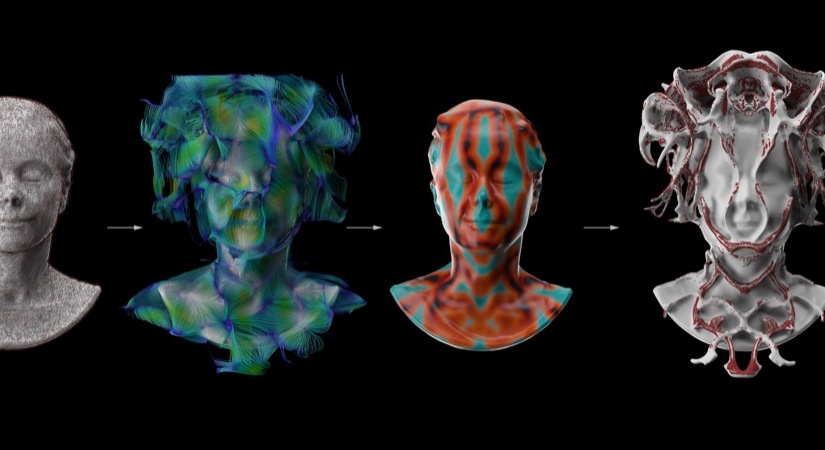

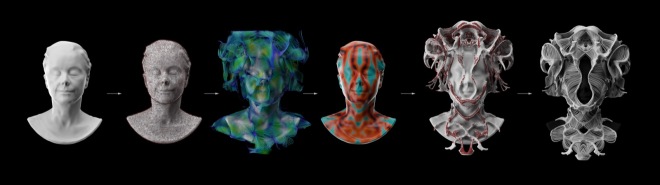

The Lab has numerous research groups, including the Mediated Matter team. This team of scientists and designers explore ‘material ecologies’ – a research area at the intersection of material science, digital fabrication, computational design, biology and design. Their week particularly focuses on how biology and nature can be used to inspire the creation and use of materials. This can then be used to then generate new forms of design and innovative material practices and processes that can then be applied in many different ways from 3D printed death masks to digitally created molten glass that transmits media to Bjork’s Rottlace mask.

Neri Oxman leads the Mediating Matter team. She has a great TED talk on the design at the intersection of technology and biology where she discusses how digital fabrication can come together and interact with the natural world.

The Cooper Hewitt collection contains numerous objects made by the Mediating Matter group. The museum also featured this video on their work as part of their Design Triennial. Please watch this – it beautiful and interesting as hell:

Material Driven (UK)

Material Driven is a platform that brings together artists, designers and architects that are producing new materials or working with pre-existing materials in experimental ways. The organisation aims to highlight ‘innovative materials, their processes of making, and the creators behind them.’ The Material Driven blog features really interesting articles and interviews with creative professionals exploring material fabrication in creative ways. I particularly enjoyed this article on Hannah Elizabeth Jones’ BioMarble material that brings together processes and practices from textiles, recycling and biodegradable matter. Last year Material Driven also put together a travelling material library called ‘Materials in Motion’ that aims to further showcase and share innovative ways creative work with materials.

ReMida Bologna (Italy)

ReMida centres are creative recycle centres that support the idea that waste such as recycled materials and industry cut-offs like plastic, wood and cardboard can be used as creative and artistic resources in communities. There are numerous ReMida centres located around the globe, including this one in Reggio Emilia:

ReMida Bologna is a part of this international network. The centre has an exceptional education programme for children, teachers and adults that allows people from different communities to creatively play and learn through the recycled materials. ReMida Bologna also has a great Instagram account (pictured below) where they post documentation from their various recycled material projects.

I love ReMida centres, or any place that promotes creative learning through recycled materials. When I scroll through the Instagram feed of ReMida Bologna I find it so inspiring to see how people are using familiar materials in unfamiliar ways. Like being creative with the combination of materials that are presented together and how they are placed and situated in a space. Loose part materials provide a special way of encouraging new processes of exploring and connecting with the world. All of these things can be used to ignite children’s imagination in new ways, generating interesting entry points for experimentation and learning.

Atelier M (Japan)

Some of the most interesting artists and educators that I ever met are renegade souls doing their own innovative things in their little corner of the world. This is how I would describe Atelier M. The organisation is essentially a children’s atelier, or art studio, located in Naha, Okinawa in Japan. I love their experimental approach to working with materials and children. It feels so fresh and creative. Atelier M also have great YouTube and Instagram pages – check these out. They speak for themselves.

I hope you find these groups as inspiring as I do. I am sure there are many more organisations out there that are doing amazing work with materials so please comment below!

Have an awesome week.

Louisa xx