This post discusses the possibilities of artworks in facilitating learning and alternate ways of imagining the world. I draw upon the work of Maxine Greene and John Dewey to explore the proposition that children’s learning through artworks has the potential to challenge dominant discourses, opening up new ways of thinking and being. There is also a resource list for educators and parents interested in incorporating artworks into children’s learning.

“It is not that the artist offers solutions or gives directions. He nudges; he renders us uneasy; he makes us (if we are lucky) see what we would not have seen without him. He moves us to imagine, to look beyond” Maxine Greene (2000, p. 276).

Artworks can be used in many ways for many different reasons in learning contexts. They offer rich possibilities for experiencing and imagining the world from new and multiple perspectives. Visual art as well as the arts more generally, have the ability to make people aware of different ways of thinking and being in the world, working against reductionist and singular ways of thinking.

Maxine Greene (2000) extends upon the word of John Dewey (1916, 1934, 1954) to argue that imagination and the arts play a critical role in the making of democratic communities. She suggests that school curriculum should aim to prioritise the ‘releasing of the imagination’ through providing rich aesthetic experiences for children. These then provide new modalities for children to sense, experience and learn through the world.

However, the mere presence of artworks in a learning environment does not guarantee that a child is encountering or imagining the world in new ways. Greene argues that if school curriculum is to support imagination through the arts, children’s encounters need to be aesthetically varied, rich and reflective. Through this, learning through artworks has the potential to challenge dominant discourses and ways of thinking. This may then encourage children to question their understandings and assumptions about the world, to think critically about what is and what could be.

Below is a list of resources for educators and parents who may be interested in incorporating artworks in children’s learning at home or in the classroom.

Resource list

Many of the major modern and contemporary art museums have online digital archives for their collections. Here are some links to my favorites:

Online art museum collections

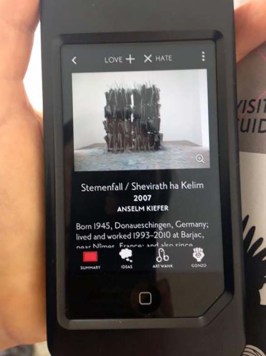

The Museum of Modern Art has made 77,000 works from 25,000 different artists available online. The search engine is easy to use and you can refine your hits using different classifications and time periods.

Tate also have an extensive online collection featuring artworks, exhibitions, videos and artist journals. The digital archive is well referenced and has many tags that are great for getting lost in amazing artwork worm-holes. The search engine is easy to use and has lots of search filter options. Tate’s most famous artworks feature extensive summaries, a copy of the artwork’s display caption as well as the techniques used to produce the artwork, for example Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ page.

- The Guggenheim also has an extensive digital archive.

Video Channels

- TateShots and TateTalks– Tate have also put together two quite an exceptional collection of video and audio recordings. TateTalks features video footage of talks and events held at the art museum. TateShots comprises of artist interviews, performance pieces (I highly recommend watching Earle Brown’s ‘Calder Piece‘), exhibition films and artist studio visits. If I had a dollar for every minute I spent watching TateShots I would be a millionaire. But I work in children’s education and the arts so maybe I shouldn’t put a monetary value on the amount of time I procrastinate.

- The Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark has a constantly growing online collection of videos from different fields such as art, architecture, music, literature and design. I love the Louisiana Channel as it features a lot of Scandinavian and European contemporary artists who I have only discovered through watching these clips.

- The art auction houses of Southeby’s and Christie’s both have YouTube channels featuring short video clips of artist interviews, studio visits and world auction records.

Online courses

- MoMA has developed three online courses that explore inquiry-led learning through artworks. Admittedly I have not had a chance to do any of these courses but I think it worth a look. The first, ‘Art & Ideas: Teaching with Themes’ uses theme-based teaching practices to support educators in incorporating modern and contemporary artworks into curriculum. Then there is Art & Inquiry: Museum Teaching Strategies For Your Classroom looks at museum education strategies for inquiry-based teaching and how these can be used in classrooms. Finally, Art & Activity: Interactive Strategies for Engaging with Art builds on content from courses one and two to explore activity-based strategies for using artworks primary and secondary lesson plans.

Article

- Here is a link to Dr. Emily Pringle’s article on ‘The Artist as Educator: Examining Relationships between Art Practice and Pedagogy in the Gallery Context.’ Emily is Head of Learning Practice & Research at Tate & also my awesome co-PhD supervisor.

References

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York, Macmillan.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. New York, Minton, Balch.

Dewey, J. (1954). The Public and Its Problems. Chicago, IL: Swallow Press.

Greene, M (2000). ‘Imagining futures: the public school and possibility,’ Journal of Curriculum Studies, vol 32(2). P.267-280.

The MONA building was also designed to naturally flood as the River Derwent rises over the next 50 years. When questioned about this in a 2014 Guardian article, Walsh said:

The MONA building was also designed to naturally flood as the River Derwent rises over the next 50 years. When questioned about this in a 2014 Guardian article, Walsh said: