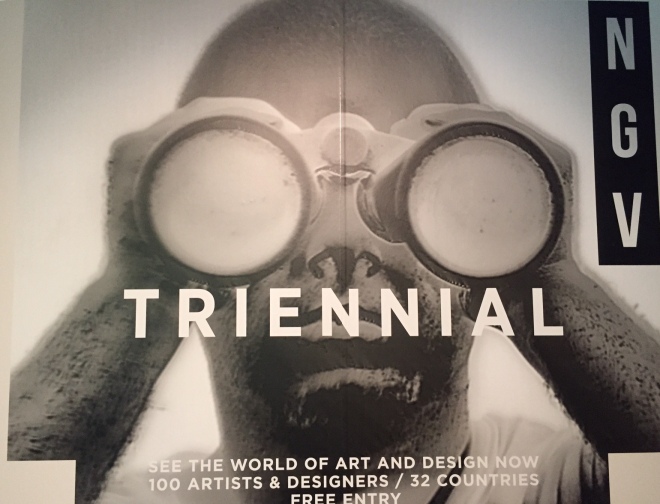

This post discusses the possibilities of materials and material play in children’s learning through art. I draw on the theories of loose parts and new materialism to argue that materials, including artworks, play an active and participatory role in opening-up divergent thinking and inquiry-led learning in schools, home and informal learning contexts such as art museums.

Why do materials matter?

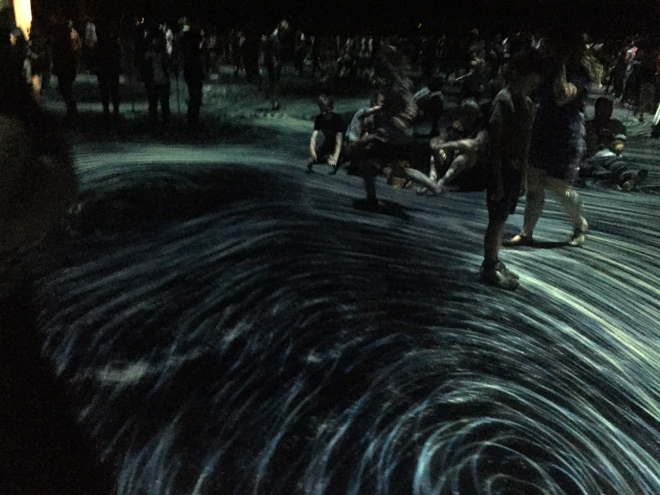

Materials and material exploration have long been a part of artistic inquiry. Since Frobel’s development of the kindergarten in the late 1700’s, they have also held an important place in early childhood settings. In the 1970’s Simon Nicholson presented the theory of loose parts – the proposition that young children’s creative empowerment comes from the presence of open-ended materials that can be constructed, manipulated and transformed through self-directed play. It is fair to say that material content, including artworks and art materials, hold tremendous possibilities for facilitating children’s inquiry-led learning in new and divergent ways. I consider materials to be one of multiple forces that learning can emerge from in an art museums. Others may include social interaction between people, spatial layout of things and the delivery of curatorial content such as through audio guides or information resources.

As reading and writing are often privileged in school curriculum, experimentation with different materials can provide new opportunities for alternate and aesthetically-driven pedagogies to be produced (check out this blog for how I define pedagogy). This is to say that different materials may encourage different ways of thinking, learning and being. For example, in a previous posts on ‘suggesting as a technique for facilitating children’s learning through art’ I talk about the different cognitive, social, emotional and aesthetic learning pathways that two different materials: plastic cylinders and large paper sheets may present. Whilst the cylinders may provoke explorations around stacking, placing, dismantling, balancing, arrangement and construction, the large paper sheet may suggest gentle movements, swaying, rolling, folding, hiding and enveloping. Through experimentation, the properties and abilities of a material may change, creating new starting points for further inquiry and experimentation.

The active role of materials in art practices and learning

In the arts, different materials such as paint, clay, paper, resin, fabric, wood or plastic can be experimented with in a myriad of ways. In art forms such as dance, live art and socially engaged practices, materials may be slightly more abstract such as the human body, sound, participants and society. I believe that art materials are not just a tool for self-expression or a thing for children to manipulate; they are an active and participatory force in the production of learning and knowledge. For example, check out this lovely video by visual artist Shirazeh Houshiary in which she talks about the active role of materials in her practice:

I really connect with this, especially the comment: “… they are not representation of the form but a pulsation of the form. I am not interested in painting. I am not interested in the processes of making in the conventional sense of representation. I am trying to get into how something works. This process has taught me a huge amount about who I am, which is surprising. It a process of learning for me more than anything else.” The paint and paintings are active, participatory and dynamic in the artist’s creative experimentation.

Art materials as an invitation to experiment

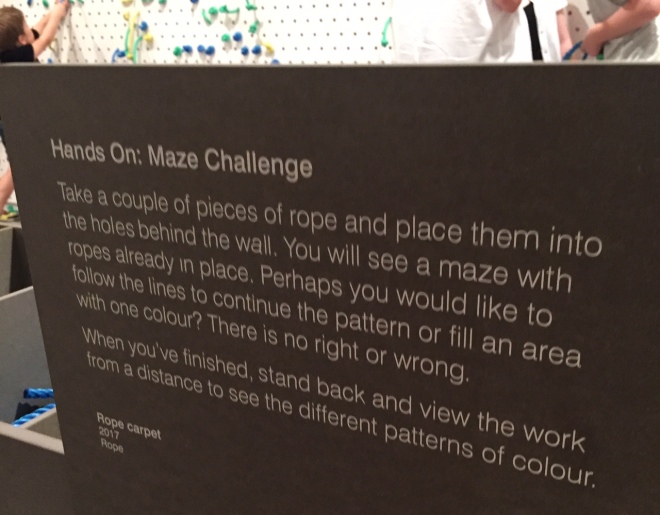

Material play has the ability to encourage emergent thinking processes, allowing children to produce new understandings as well as experiencing the world from multiple perspectives. However, materials also have the ability to be used in static and predictable ways that shut down creativity and divergent thinking. Whilst I do love Instagram feeds and craft blogs that share ideas for children’s art activities, I am cautious that these may unintentionally encourage imitation and fixed ways of using materials with children. This may then reduce the ability for experimental thinking and practices to emerge.

The challenge to me – and everyone working in learning settings with children – is to keep experimenting, keep questioning, keep venturing into the unknown and the yet-to-be-discovered of art, play, materiality and pedagogy.

I am sure many of you have really interesting insights on this topic and it would be lovely to hear them. Why is children’s play with materials important to you? What are your favorite materials to experiment with?

Further links

The Institute of Making at the University College of London has a great online material library – perfect for anyone who likes to nerd out about different material forms: http://www.instituteofmaking.org.uk/materials-library

My friend Nina Odegard has written a brilliant article on children’s learning with recycled ‘junk’ materials. Nina formally ran a creative recycle centre in Norway: http://www.academia.edu/14201590/When_matter_comes_to_matter_working_pedagogically_with_junk_materials

Professor Pat Thomson, Nina Odegard and I recently did a conference symposium on children’s material play. Check it out: https://louisapenfold.com/2017/12/06/childrens-learning-with-new-found-and-recycled-stuff-symposium-at-aare/

Here is the link to my blog post on Simon Nicholson’s theory of loose parts: https://louisapenfold.com/2016/05/23/simon-nicholson-on-the-theory-of-loose-parts/

I also love the book ‘Encounters with Materials in Early Childhood Education’ by Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw, Sylvia Kind and Laurie Kocher.