This post looks at Serpentine Galleries’ ‘Play as Radical Practice’ toolkit, a creative resource produced between the Gallery’s learning team, artist Albert Potrony and the Portman Early Childhood Centre (UK).

In 2014, the Serpentine learning team commenced a series of artist residencies with the Portman Early Childhood Centre in Westminster, London (UK) run as part of their Changing Play programme. Changing Play aims to explore the possibilities of play through exploring current practices and alternate re-considerations of early childhood education.

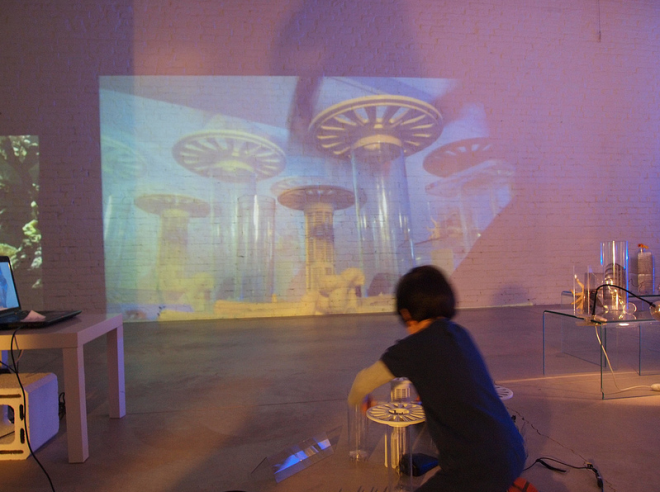

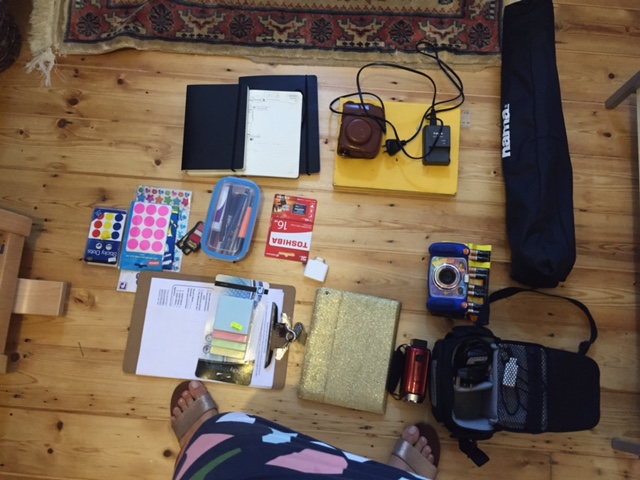

Last year, artist Albert Potrony undertook a 12-week residency at the Portman as part of the programme in which he worked collaboratively with children, staff, parents and Serpentine to explore the potential of free play in the school system. Throughout the residency, Albert created a series of material-led play spaces featuring matter such as recycled tubes, plastic sheets, ropes and reflective plastics. During the sessions, children were encouraged to creatively explore the materials alongisde peers and adults through play. Before, during and after each session, the artist, Portman staff, parents and Gallery team engaged in critically reflective discussions that considered the relationships between the programme’s various components such as the materials, curriculum, people and pedagogical underpinnings. The ‘Play as Radical Practice’ toolkit is a direct product of these collaborative discussions.

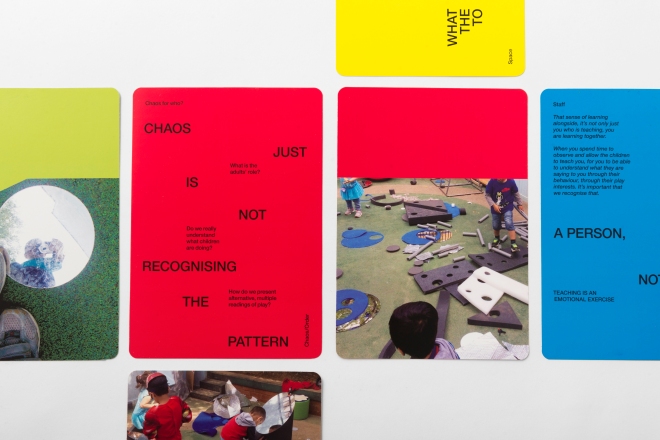

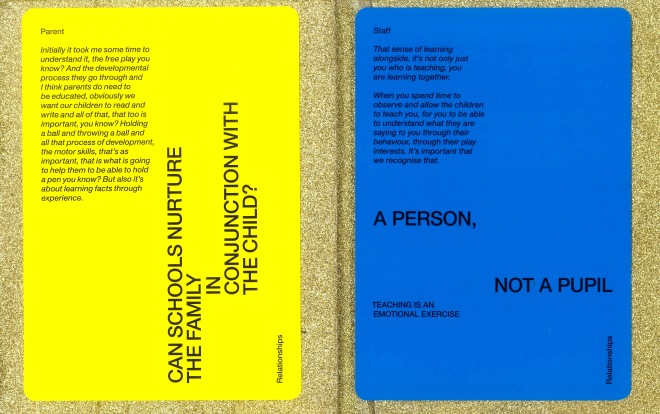

The toolkit is comprised of three main parts: a booklet, a 24-piece card game (pictured below) and an accompanying film. These work together to share and further consider the imagery, questions and ideas generated from the residency. The toolkit also seeks to support early educators to form solidarities with the children they work with and to advocate for free play in the state school system. This is done through taking a individuals taking position as well as including thoughts and questions from multiple perspectives.

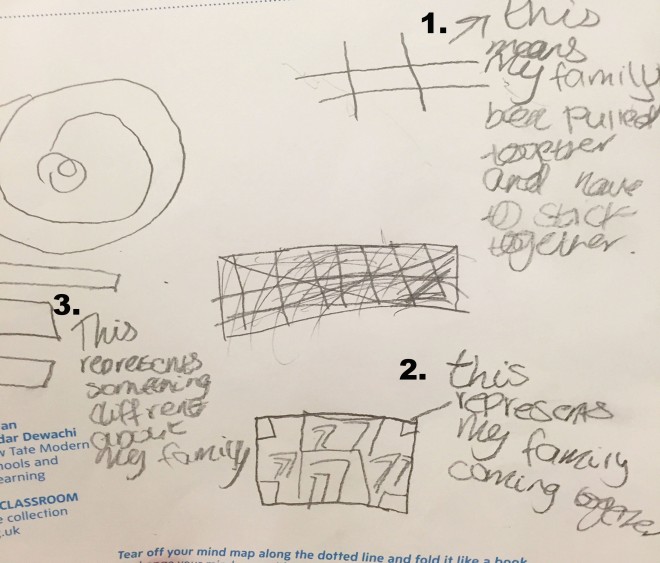

I really like the way the card game explores the residency’s emergent debates and ideas from multiple perspectives including children, parents, curators, the artist and centre staff. Each of the cards in the game features an image and provocation such as field notes, a quote and/or question. For example, one card combines an image of a child and staff member playing with the artist’s materials in the nursery. A quote from a Portman staff member is then presented alongside the image with four interconnected questions:

” ‘They are different children with different members of staff. It’s really interesting, when you read the school reports you think ‘I don’t see him like that at all.’ He may be really chatty with me and really quiet with someone else and also the children behave differently depending on who is present, which is that thing about stepping away from them and letting them play by themselves as part of that witnessing.’ Staff

What is witnessing? Who does it? What does it mean? Witnessing as assessment? “

These work together to situate the emergence of the educator’s idea around the standardisation of learning within the specific context that it was produced. Furthermore, the card invites the reader, or ‘player’ of the card game, to extend, challenge or support the teacher’s experience through critically thinking about the questions themselves.

Each card is further divided into key themes such as space, relationships, standardisation and chaos/order. Each one of these themes prompts deeper consideration and re-considerations around the imagery, quotes and questions featured in the toolkit. The accompanying booklet investigates these themes more extensively alongside quotes from key early childhood and play theorists such as Hillevi Lenz-Taguchi, Tim Gill, Simon Nicholson and Arthur Battram. You may also come across the introduction I wrote for the toolkit in the booklet, lol. I do wish to point out that my role on the programme is insignificant in comparison to the amazing educators, curators, artists, children and parents who worked together on an ongoing basis to produce the complex conversations, thinking and practices throughout the residency.

The toolkit booklet can be downloaded from the Serpentine website here. A limited number of printed toolkits are available free of charge from the Serpentine learning team. For a copy, please email: jemmae@serpentinegalleries.org . The Play As Radical Practice film will be available to view on the Serpentine website in the near future. An interim report of Serpentine’s World Without Walls programme, including Changing Play, can also be downloaded from the University of Nottingham’s Centre for Research in Arts, Creativity and Literacies website here: worldwithoutwalls_interimresearchreport_final-copy

![FullSizeRender[1]](https://louisapenfoldblog.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/fullsizerender1.jpg?w=660)

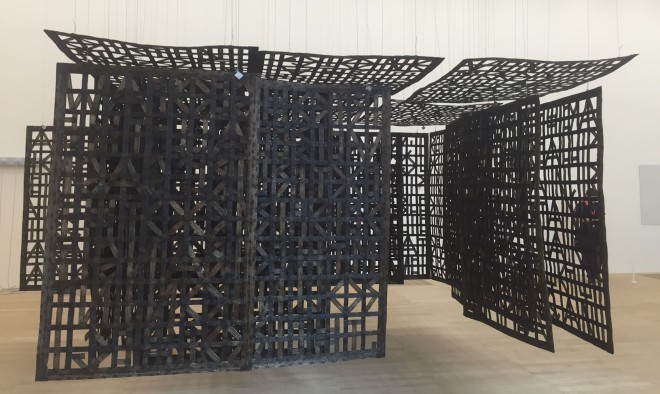

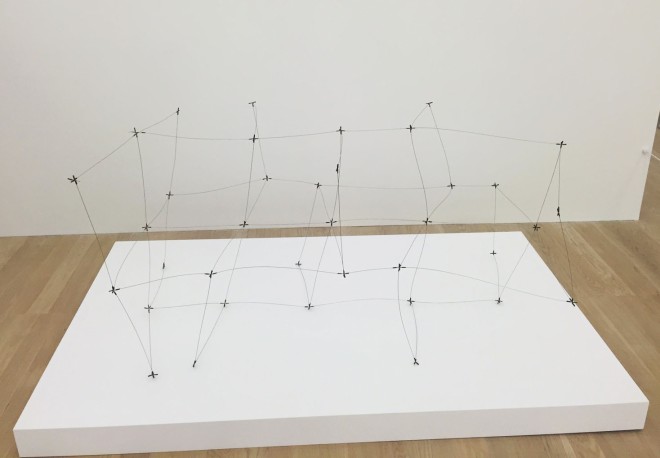

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Horizontal Square Reticularia 71/10, 1971. Steel rods and metal beads. Tate collection.

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Horizontal Square Reticularia 71/10, 1971. Steel rods and metal beads. Tate collection.